The Singularity is...

Hi there,

Fancy a fabulous and profound read and unique take on the Singularity, AI, the technological age and the Exponential Age…?

That’s a yes?

Well then you will enjoy (and possibly be terrified by) this essay from David Mattin, first published in the Exponentialist in January.

Enjoy…

Raoul

The Singularity is Now

I’d like us to step back and think more expansively about the Exponential Age and its ultimate meaning.

With that in mind I want to examine an idea that’s woven deeply through our project. An idea, that is, that forms part of the DNA out of which the Exponentialist is made, and that underlies much public thinking on the ongoing technology revolution and our shared future.

I’m talking about the Technological Singularity.

Once fringe at best, the idea that is a coming Singularity has crept into the popular consciousness across the last couple of decades. And that process has accelerated since 2020, and the advent of GPT-3.

In 2024, Singularity-fuelled thinking is a big deal. That’s principally because of the AI moment we’re all living through, and the seemingly raised chance that we may soon develop something we can meaningfully call Artificial General Intelligence, or AGI.

I believe that the idea of a coming Technological Singularity is legitimate. But I think the idea is much misunderstood. And what’s more, even the mainline accepted definition of the Singularity — which we’ll get into soon, and hinges on the advent of superintelligence — is not technologically or historically coherent.

I want to put forward a revised vision of the Singularity. That vision is underpinned by the idea that the Singularity isn’t an event that will, as many proponents suggest, fall out of the sky in 2045 or at some later date. Rather, it’s a world-historical process that we are already living through.

To understand the Singularity this way is to reframe our relationship with the ongoing exponential technology revolution, and our view of where we stand in the great flow of human history. And that has real implications for what we should pay attention to, and what we should do, now.

We can all feel the conversation on these issues heating up.

Right now Sam Altman only has to sneeze and half of X is speculating that OpenAI has built a superintelligence. And online intellectual currents are gravitating towards questions around our relationship to technology. See, for example, the breakthrough of the effective accelerationism movement (e/acc) on X in 2023; more on that later.

This conversation is only going to get noisier. The issues at hand will only become more urgent. I want we Exponentialists to have a robust take on it all all; a structured view of the terrain that helps us sort sense from nonsense.

Yes, that can help shape our investment decisions. But in the end, this is about ultimate questions. What it means to be human. Our purpose here. And our relationship with the world we find ourselves in.

As 2024 dawns, and the Exponential Age becomes tangible for billions, there’s no better time to dive in. So grab a coffee, lean back, and let’s start.

*

A Brief History of the Singularity

If I’m to offer a radically revised conception of the Technological Singularity, we first need to establish the core context. Specifically we need to know: what is the Singularity, as commonly defined?

I vividly remember first reading about the Singularity in the early 2000s. Back then it was an idea hidden in niche corners of the internet: blogs about existential risk by obscure academics, or about an emerging techno-philosophical movement that called itself transhumanism.

I was just out of college, fascinated by the broad sweep of human history, and waking up to the idea that this network growing around us — this new thing called the internet — was the story of our lifetimes.

The idea of a Technological Singularity blew my head off. It still does. But to understand why I’ve come to believe that the idea in its current mainline incarnation is flawed, we need briefly to examine the history of this idea. We need to understand how it came to be what it is.

The history of thinking on the Singularity stretches across a complex network of thinkers, and can be traced back far deeper into the past than the 20th-century. But I’ll focus on the four key figures who did most to shape the idea in its current form. They are the polymathic genius John von Neumann, British mathematician and computer scientist IJ Good, US computer scientist and science-fiction writer Vernor Vinge, and the popular futurist Ray Kurzweil.

Von Neumann was a mercurial titan of 20th-century mathematics and theoretical physics, best remembered for his work on the Manhattan project and game theory. And it’s Von Neumann who is believed to have first described a technologically induced ‘singularity’.

This comes to us not in Von Neumann’s own writings, but via a 1957 obituary by the mathematician Stanislaw Ulman. Recalling their regular talks, Ulman mentions:

‘One conversation centered on the ever accelerating progress of technology and changes in the mode of human life, which gives the appearance of approaching some essential singularity in the history of the race beyond which human affairs, as we know them, could not continue.’

It’s a brief but all-important first glimpse of the idea. Von Neumann’s leap to a ‘singularity in human affairs’ laid the foundation stone.

Remember, Von Neumann was a theoretical physicist. When he talked about a singularity, he did so with a precise understanding of the word.

In physics, a singularity is a theoretical entity found at the heart of a black hole. It’s a place where gravity becomes so intense that spacetime folds in on itself to create what is seemingly impossible: an object that has zero volume and infinite density. A point in spacetime, in other words, where the rules that govern physical reality simply break down.

And that’s what Von Neuman was talking about when he speculated on a technologically-induced ‘singularity in human affairs’. He meant a threshold that marked change so transformative that everything we know about human history — all the old models, rules, and norms that shape our collective and individual lives — no longer pertain. The Singularity, for Von Neumann, was a definitive break-point in the human story. Beyond it lay the unimaginable.

We don’t hear much about the Singularity again for a while. But in the meantime, the story was moved on in an indirect but consequential way by the British mathematician IJ Good.

A statistician of genius, Good worked with Alan Turing at Bletchley Park during WWII, and played a crucial role in breaking the German Enigma code. After that, he followed Turing into computer sciences. Here he is at the chessboard — he’s closest to the camera:

In 1966 Good published a now-iconic essay called Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine. It contained these lines:

‘Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an 'intelligence explosion', and the intelligence of man would be left far behind.’

Good had realised the insane recursive power of superintelligence to create even more powerful superintelligence, in an endless loop. His conception of the resulting ‘intelligence explosion’ — which would see intelligent machines render we humans as children in a world we could no longer understand — became deeply woven through conceptions of the Singularity.

That interweaving didn’t occur on its own. It happened over time, and most famously via the work of the maths professor and science-fiction writer Vernor Vinge.

In the January 1983 edition of the US science magazine Omni — it ceased publication in 1997 — Vinge wrote about the idea of a coming Singularity. And crucially, he linked it directly to the advent of superintelligence and the intelligence explosion that would result:

‘We will soon create intelligences greater than our own. When this happens, human history will have reached a kind of singularity, an intellectual transition as impenetrable as the knotted space-time at the center of a black hole, and the world will pass far beyond our understanding.’

This was a hugely significant step in the story. It was the first time anyone had linked Von Neumann’s conception of a ‘singularity in human affairs’ with IJ Good’s hypothetical intelligence explosion.

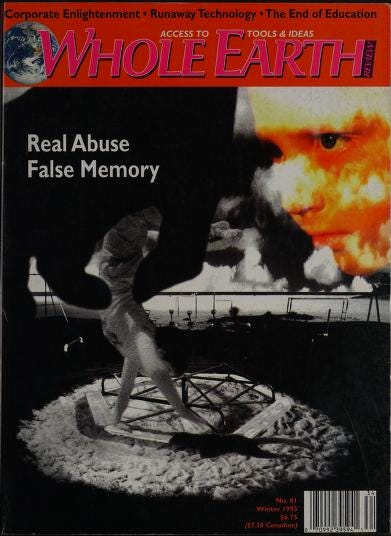

And in a 1993 essay in the Winter issue of the iconic Whole Earth Catalogue Vinge went further, arguing that it was the fusion of human intelligence with machine intelligence that must really define the Singularity.

‘From the human point of view this change [the fusion of human and machine] will be a throwing away of all the previous rules, perhaps in the blink of an eye, an exponential runaway beyond any hope of control… Von Neumann even uses the term singularity, though it appears he is still thinking of normal progress, not the creation of superhuman intellect. (For me, the superhumanity is the essence of the Singularity. Without that we would get a glut of technical riches, never properly absorbed.)’

A version of his essay eventually went viral on the early web, consolidating Vinge’s thinking as the mainline interpretation of the Singularity.

Vinge’s essay said the fusion of human and machine intelligence would lead to a ‘post-human’ era, and raised the possibility that this could be disastrous for we humans: ‘the physical extinction of the human race is one possibility’. In this way, the essay helped shape our current debate around AI doom, and is an ancestor to the post-human era speculations that Yuval Harari deploys in his smash hit Homo Deus.

Finally, in 2005 the futurist Ray Kurzweil published the book that pushed all these ideas into the tech-literate mainstream. The Singularity is Near endorsed Vinge’s conception of the Singularity as the coming fusion of human and machine intelligence. Never one to shy away from bold claims, Kurzweil declared that the Singularity would arrive in 2045. It’s a prediction he stands by today.

And so our contemporary conception of the Singularity was, at last, fully formed.

Kurzweil rounded out the idea as we know it today by gesturing, also, to its religious undertones. Under this view the fusion of human and machine intelligence is only the first step in a broader process that sees intelligent life travel to the stars, such that the entire universe eventually becomes a single, vast, and sentient superintelligence. These ideas drew on the mid 20th-century Catholic philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and his theory of the Omega Point: an ecstatic vision of final cosmic unification.

And with that our brief history of the Technological Singularity is complete.

But this history, as I made clear at the start, has been established for a reason. We’ve made a tour through some formidable thinkers here, and now I intend to tangle with them.

Because I believe that the conception of the Singularity we’ve ended up with via these thinkers — the conception that reigns supreme in 2024 — is far from ideal. It’s not the most coherent, or useful, version of the idea possible. So I’m going to suggest a new one.

Sure, it’s a bold move. But what’s the New Year for here at the Exponentialist if not for sharing our boldest thinking?

*

The Real Beginning

My conception of the Singularity gets back to the roots of the idea. That is, Von Neumann’s thinking on a definitive break point in human affairs; an event after which all old rules break down.

I want that original definition of a ‘singularity in human affairs’ to ring in our ears while we look at some charts. All these are from the brilliant Our World in Data.

First, before around 1820 the vast majority Earth’s population lived in what we’d now call grinding poverty:

Remember, the chart above shows only the downward swing that began in earnest around 1800. Before that, the graph would be flat and above 75% for thousands of years. During that time, nothing changed. Harsh material conditions were the default norm for almost all humans all through our history.

Here’s another fascinating chart. Again, something miraculous starts to happen around 1800:

Here’s another; this is the longterm story on per capita energy consumption.

Again, if we took it back in time we’d see the line lie flat for tens of thousands of years. According to the energy expert Vaclav Smil, citizens in Paris in 1900 had the same per capita energy use as the inhabitants of ancient Rome. Around 1900, dramatic change begins:

And here’s another. This one gives us a great view of the broad sweep of human history, and sudden change in the 19th-century:

Child mortality is a great indicator of general human flourishing. And in pretty much every historical society we have evidence of, from prehistoric hunter gatherers to 18th-century Venice, it hovered between 40% and 50%. In the US in 1800 infant mortality was around 47%; that’s right, in north America just 200 years ago more than 450 out of every 1,000 children died before the age of five, an ongoing catastrophe that seems unimaginable to US citizens now.

Today, global child mortality stands at around 4%. A transformation beyond words. Not everywhere has shared equally in the progress. But even the nation with the highest rate, Somalia — where infant mortality is at 14% — has been changed beyond recognition in this regard.

Why am I showing you these charts? To stress a simple but powerful point.

Our species evolved around 200,000 years ago. For all of human history, certain truths about our existence were stable. Before 1800 almost everyone lived in what we would now call grinding poverty. Reading and writing were not technologies available to early humans, but even once they'd been invented hardly anyone had access to them. And almost half of all children died in infancy, always.

Those truths pertained for 99.9% of our shared story. Then around 1800, something happened. And we all know what that something was. The Industrial Revolution.

Historians argue about the spark that lit the fuse. In his brilliant book Novacene, the engineer and philosopher James Lovelock points to Thomas Newcomen and his 1712 atmospheric engine: the first machine to harness steam and turn it into useful mechanical work.

Wherever you mark the precise start, it’s broadly agreed that in England in the 18th-century, something of epoch-defining significance took root. Humans learned to harness energy, tools, and mechanical processes in powerful new ways. A process of industrialisation began that, slowly at first and then with gathering speed, travelled across much of the world and transformed the material conditions of life. And that transformed everything.

To get an idea of the scale and speed of this transformation, let’s look at one last chart. England is unique in having collected data that allows us to estimate adjusted GDP all the way back to the 13th-century:

We are all here to understand technology-fuelled exponential change. Here is perhaps the most significant example ever — because it underlies all the rest.

The dramatic upswing in material affluence depicted here was echoed across the Global North and eventually beyond. And it tells the story of the modern world. Dramatically raised standards of living. Vastly extended average lifespans. The transformation, in the industrialised world, of infant death from everyday norm to rare tragedy. Mega-cities, mass education, pop culture, hyper-individualism, and a planet turned into a village. It’s all latent in that chart.

By convention the Industrial Revolution ended around 1840. And the Second Industrial Revolution – the one characterised by the advent of mass production and electrification – started around 1870. Then came computers and the Third Industrial Revolution. Now, many think we're living through a Fourth Industrial Revolution powered by AI, robots, and new genetic technologies.

Those terms do correspond meaningfully to visible stages in our technological and industrial development. But pull back the lens and look at all this from the point of view of 200,000 years of human history, and it makes more sense to view them as four stages of a single historical process. That is, four stages of one Industrial Revolution that began around 1800 and is ongoing.

And now, at last, I can come to the fundamental point I’m driving at here.

Remember Von Neumann’s source-code thinking about the Singularity as a definitive breakpoint in human affairs. If you adhere to that, then the Industrial Revolution we’re living through — and the condition of modernity it has created — is the Singularity.

If the word singularity is to have any coherent meaning, it must be as Von Neumann understood it: a point at which all the old rules break down. The charts above show with visceral power how technology-fuelled modernity is just such a point when it comes to the human story. For 200,000 years the fundamental conditions of our collective existence were stable. And then boom!

Yes, this is a deeply non-standard analysis. I promised as much.

We’re so deep in modernity — so immersed in the totalising world it has made — that it’s almost impossible for us to remember that this is a world utterly transformed. It would be unrecognisable to our great-grandparents, let alone to all those who lived before them.

My interpretation of the Singularity, as I’ve made clear, is founded in Von Neumann’s original breakpoint thinking. This means I think Vinge took us down a misguided path when he tied the Singularity to a human-machine intelligence fusion such that they came to be understood as essentially the same idea.

I’m emphatically not saying that superintelligence, or the fusion of human and machine intelligence, are not big deals. They’re transformative, and in some deep sense the terminal station of the long journey through modernity that began with the steam engine (more on that later). But that’s the point: we need to understand them as part of a larger process that is the unfolding Singularity.

The Singularity isn’t an event that will suddenly fall out of the sky in 2045. Rather, it’s a process we already live inside. The Singularity is now, and we’re among the lucky few humans who get to witness it firsthand. When we see the Singularity this way, it lends us a radical new perspective on both our relationship to the broad sweep of history and on crucial technological megatrends unfolding today.

Viewing the Singularity this way — as a process unfolding across a few hundred years — makes far more historical sense. Sure, the Singularity has always been modelled by its chief proponents as more of an event than a process. But across the great span of human history, which stretches 200,000 years into the past and potentially millions of years into the future, a few hundred years is an ‘event’. From that perspective, it’s a flash that happens once and changes everything.

This isn’t just a theoretical shift. It has real implications for the way we collectively manage the next few years. In particular, for when it comes to navigating the machine intelligence revolution that is now gathering speed.

When we understand the Singularity properly, we’re empowered to better understand and navigate the emergence of machine superintelligence. We can better understand its nature as a historical event. The risks it presents. And a little of how it will feel to live through its emergence.

So let’s get into all that.

*

Human After All

So how does our new view of the Singularity as a process we’re already inside — one that began with Newcomen’s steam engine — change our perspective on events unfolding now? And in particular on the AI revolution that began with the arrival of GPT-3 in 2020?

Today, two variants of the mainline interpretation of the Singularity occupy the popular consciousness. In most people’s minds — including plenty of technology journalists — the details are hazy and the two variants blur together.

Still, we’ll treat them separately. This section will contain some of my most controversial analysis. I present it with conviction; if you disagree, we can have a brilliant discussion about it all in this month’s AMA. These kinds of discussions are a big part of what the Exponentialist is all about.

First, there’s the variant that simply equates the Singularity with the arrival of superintelligence and a resulting ‘intelligence explosion’. A world in which humans are no longer the most intelligent entities would be, so runs this line, a world utterly transformed.

And there’s no doubt about it: the creation of superintelligent machines would be an epoch-making achievement. But would it transform everything we know about human life? Does it constitute the definitive breakpoint that is the defining characteristic of a singularity? Apply our new perspective — the Singularity as a process that we’re already living through — and a new and more coherent answer becomes apparent. The answer has two dimensions.

First, there’s the argument around complexity. Proponents of this variant of the Singularity say superintelligent machines would mark a breakpoint because they’d immerse us in a world in which human intelligence — in which our intelligence and agency — is no longer in the driving seat. We’d be as children, wandering through a world beyond our control and comprehension.

But step back and consider: that is the condition of life already for any citizen of an advanced industrialised nation. We already live inside a techno-modernity far beyond the comprehension or control of any of us, even our most powerful leaders. One in which deep structural forces and technologies seem to have an agency of their own, which operates beyond ours.

This world was built by the industrial revolution and the great Leviathans that are states and corporations — forms of artificial intelligence all of their own, created by the unification of millions of networked people. These Leviathans have a strange superintelligent agency of their own, and have created a world in which bewildering complexity and absence of control is, for each of us, the central condition. We are already as children inside this world.

Superintelligent machines would render that condition far more acute, yes. But they wouldn’t, taken alone and by necessity, change its fundamental nature.

What’s more, when we view the Singularity as a process now in train we become more able to recognise another core truth about superintelligence.

We’re more likely to experience the arrival of superintelligent machines by degrees — again, as a process — than we are as a sudden event that falls out the sky. Remember, there’s no consensus on what we even mean by AGI, let alone any clear means to tell whether or not it has arrived. Much as the maturation of a person from babyhood to mature intelligence unfolds to us not as a sudden event but as a process, so too will the emergence of machine superintelligence.

This isn’t just a theoretical distinction; it has consequences for what we pay attention to and what we do collectively now.

Sam Altman and other AI leaders want us to believe that the core danger is AGI that presents itself to us suddenly and runs out of control. When we view the Singularity as a process already unfolding and understand the emergence of superintelligence as part of that process, a more pressing risk floats into view. That is, high and generalised intelligence that we can control and that remains under the control of a narrow techno-elite that uses it to impose increasing economic and cultural hegemony over the rest of us.

That’s why I’m so convinced that open-source AI for the people is a crucial movement for the coming years. And some time soon we’ll go deeper on all that and the key players at work there, including Stability AI.

But let’s turn to the second and more comprehensive mainline interpretation of the Singularity, as it was established in the previous section. This is the view that sees the Singularity as defined by the fusion between human intelligence and machine intelligence, and the consequent establishment of a post-human era.

There’s no doubt the case for human-machine fusion as a definitive breakpoint in human history is compelling. We’ve established just how powerfully the industrial revolution and modernity transformed the human story; but it did that by changing the world that we inhabit. Throughout that process we humans have remained, at heart, the same. We meet the modern world with the same basic physical and cognitive equipment as the inhabitants of the bronze age. Human-machine fusion is different. It’s not about changing the world; it’s about fundamentally changing us.

So why, then, do I still argue that this kind of human-machine fusion isn’t best understood as the Singularity? That, rather, it should be seen as part of an ongoing Singularity that we’re already inside?

Again, the view of the Singularity as a process is vital.

As we’ve seen, proponents of this mainline human-machine fusion version of the Singularity tend to model it as a sudden event. Yuval Harari’s Homo Deus, which says human-machine fusion will spark the arrival of the post-human era, tends towards the same model. Get ready, the post-human era is about to land, this is the end for humans, this is the moment that changes everything!

The truth is more complex. And again, a view of the Singularity as an ongoing process that we’re already inside allows us a fruitful perspective on that truth. In short, it empowers us to see that even the advent of post-humanity won’t occur as a definite breakpoint ‘event’, but as an unfolding.

Even once technologies of machine-human intelligence fusion are safe and effective, only a minority — at least, for a considerable time — will have access to them. Still fewer will choose to use them. The result will not be in any meaningful sense a post-human era. It will be best understood as the start of a multi-human era; one in which a few are some new and technologically enhanced species, but the great majority are plain old homo sapiens as we’ve always known them.

Of course, the splintering of the human family into multiple branches would be a monumental event in its own right.

But the new era it represents will still be more human than post-human. And it will present a recognisably human challenge. That is, the need for sentient creatures — in this case humans and post-humans — with radically different outlooks and value systems to find ways to live alongside one another.

In what is called the post-human era, this will be the fundamental challenge: the coexistence of humans and varieties of post-human. And this is a set of circumstances that, in the end, couldn’t be more human in its nature. Conflict between people with different outlooks and value systems, and the many efforts we make to ameliorate those conflicts, has always been the defining feature of our collective lives.

You can even see the earliest seeds of this conflict between humans and post-humans being sown now, in the new intellectual currents around technology brewing online. Look at effective accelerationism (e/acc) and its stated determination to accelerate towards superintelligence and human-machine fusion as fast as possible:

And look, on the other hand, at the degrowth movement, which says we should put the brakes on techno-modernity and revert to more traditional modes of human existence.

These movements are both founded in real and legitimate dimensions of our shared human nature: the quest to be more — to be infinite — and the desire to lean into our creaturely, embodied and organic selves. The conflict between these two sets of values rages inside each of us. And now, as the prospect of machine-human fusion grows closer, it is becoming an authentic and practical political issue.

Across the coming years, conflict between those who want to be infinite — and see superintelligence as a route to that destination — and those who want to remain creatures will only grow more acute. Both sides have legitimate and coherent, but radically different, views of what it means to be human and how to live our best lives. When the supposed post-human era finally does arrive, this will be the central political question: how do these two groups — let's call them People of the Machine and People of the Earth — live well together?

We’ll have to marshal all our reserves, and the best of our legacy of pluralism, to find new answers. If AI progress continues the way it’s been going, this year’s coming Presidential election could well be the last in which superintelligence and human-machine fusion isn’t the dominant issue.

These are perspectives on the coming of superintelligence, and on machine-human fusion, made possible when we reconfigure our understanding of the Singularity.

The definitive breakpoint in the human story isn’t an event in our future. It’s not about to fall out of the sky, be announced on X, or get leaked via WhatsApp messages between team members at OpenAI. It’s a world-historical process happening now; it is the stupendously powerful and transformative industrial revolution we’re living through. And when we understand this we’re allowed new and more accurate visions of what is ahead and how we live through it.

For our community, that’s a huge deal. I mean, it’s a huge deal for everyone. They just don’t all realise it yet.

And that’s where I want to end. With some reflections on what this means for we Exponentialists, and for all of us.

*

Alpha and Omega

First, a clarification. I’ve stressed this already but it bears repeating. I’m not downplaying the advent of superintelligence or human-machine intelligence fusion. If and when they come they will of course be a stupendously, mind-bendingly big deal.

I’m just saying they’re not, under the most coherent model available to us, the Singularity.

Under my model human-machine fusion still has a special status. It’s best understood as in some deep sense the terminal station, or zenith, of the Singularity process that was set in train by a handful of proto-industrialists in 19th-century England.

Second, how do we mesh this new understanding of the Singularity with the model that brings our community together? The model, I mean, that is the Exponential Age?

If we accept the view of the Technological Singularity I’ve outlined here, then we see that the Singularity is in essence a process of exponential techno-social progress: a liftoff that began around 1800 and fundamentally changed everything about the human condition.

So, it’s been happening for a while and is ongoing. But remember, we humans are terrible at an intuitive understanding of exponentials.

Exponential progress is slow — often imperceptible — at first. It’s easy to ignore it, or view it as stable and predictable linear growth. But it gathers pace and then all of a sudden comes to feel terrifying; as though it's moving at warp speed.

And that’s what’s happening to us now. We are entering the warp speed phase of the techno-social process that started some 250 years ago. Not only will we be living on an exponential curve, we’re going to feel it. The products of warp speed change will reshape everyday live, dominate our culture, and strain our politics to and probably beyond breaking point. That’s why the coming decades will truly be an Exponential Age.

It puts we inhabitants of the 21st-century in a remarkable and privileged position. We get a ringside seat to the most significant epoch in human history: the warp speed phase of the Singularity. It’s that, and nothing less, that the Exponentialist was convened to watch and understand.

And, as we’ve seen in this essay, it presents us with daunting challenges.

I’ve said that in the coming post-human era — really still more of a human era after all — the fundamental challenge will be for People of the Machine and People of the Earth to live well together.

What that demands, in the end, is a new account of ourselves and our ultimate relationship to the world we inhabit.

Those who see fusion with technology as a route to infinite, all-knowing transcendence must be able to answer two questions. What, in the end, are they transcending towards? And why? On the other hand, those who seek to remain resolutely human, to lean back into our embodied and organic selves, must be able to explain: what is so important, so valuable, about the human anyway?

On both sides this requires a renewed vision of what we humans really are. Of our purpose here, and our ultimate relationship to the cosmos we find ourselves in.

The old religions once supplied such an account. For many inhabitants of modernity, the scientific revolution dismantled it. Now we must build anew. What we must make is nothing less than a religion of the future. A religion that can accommodate the impossible-yet-real process that is the Singularity.

This, in the end, is the demand that the Exponential Age makes of us all.

That’s the thing about technology. Think about it hard enough, and you always end up thinking about us. About what it means to be human. You end up staring in the mirror.

To get much more like this, you’ll want to join the Exponentialist. And you can see whether it’s the right fit for you with a trial, available through the button below.

What a fabulous article! I love this perspective. It gives me back a sense of choice and control - whether I actually have it or not :).

“The Singularity is now” works but you should call it the Industrial Phase Transition, which is what it actually is. The only slope that matters next is who controls compute, power, and data. Think political, maybe a narrow techno-state cartel.

Markets will price that control long before they understand it.