Hi there,

Fancy a fabulous and profound read and unique take on the Singularity, AI, the technological age and the Exponential Age…?

That’s a yes?

Well then you will enjoy (and possibly be terrified by) this essay from David Mattin, first published in the Exponentialist in January.

Enjoy…

Raoul

The Singularity is Now

I’d like us to step back and think more expansively about the Exponential Age and its ultimate meaning.

With that in mind I want to examine an idea that’s woven deeply through our project. An idea, that is, that forms part of the DNA out of which the Exponentialist is made, and that underlies much public thinking on the ongoing technology revolution and our shared future.

I’m talking about the Technological Singularity.

Once fringe at best, the idea that is a coming Singularity has crept into the popular consciousness across the last couple of decades. And that process has accelerated since 2020, and the advent of GPT-3.

In 2024, Singularity-fuelled thinking is a big deal. That’s principally because of the AI moment we’re all living through, and the seemingly raised chance that we may soon develop something we can meaningfully call Artificial General Intelligence, or AGI.

I believe that the idea of a coming Technological Singularity is legitimate. But I think the idea is much misunderstood. And what’s more, even the mainline accepted definition of the Singularity — which we’ll get into soon, and hinges on the advent of superintelligence — is not technologically or historically coherent.

I want to put forward a revised vision of the Singularity. That vision is underpinned by the idea that the Singularity isn’t an event that will, as many proponents suggest, fall out of the sky in 2045 or at some later date. Rather, it’s a world-historical process that we are already living through.

To understand the Singularity this way is to reframe our relationship with the ongoing exponential technology revolution, and our view of where we stand in the great flow of human history. And that has real implications for what we should pay attention to, and what we should do, now.

We can all feel the conversation on these issues heating up.

Right now Sam Altman only has to sneeze and half of X is speculating that OpenAI has built a superintelligence. And online intellectual currents are gravitating towards questions around our relationship to technology. See, for example, the breakthrough of the effective accelerationism movement (e/acc) on X in 2023; more on that later.

This conversation is only going to get noisier. The issues at hand will only become more urgent. I want we Exponentialists to have a robust take on it all all; a structured view of the terrain that helps us sort sense from nonsense.

Yes, that can help shape our investment decisions. But in the end, this is about ultimate questions. What it means to be human. Our purpose here. And our relationship with the world we find ourselves in.

As 2024 dawns, and the Exponential Age becomes tangible for billions, there’s no better time to dive in. So grab a coffee, lean back, and let’s start.

*

A Brief History of the Singularity

If I’m to offer a radically revised conception of the Technological Singularity, we first need to establish the core context. Specifically we need to know: what is the Singularity, as commonly defined?

I vividly remember first reading about the Singularity in the early 2000s. Back then it was an idea hidden in niche corners of the internet: blogs about existential risk by obscure academics, or about an emerging techno-philosophical movement that called itself transhumanism.

I was just out of college, fascinated by the broad sweep of human history, and waking up to the idea that this network growing around us — this new thing called the internet — was the story of our lifetimes.

The idea of a Technological Singularity blew my head off. It still does. But to understand why I’ve come to believe that the idea in its current mainline incarnation is flawed, we need briefly to examine the history of this idea. We need to understand how it came to be what it is.

The history of thinking on the Singularity stretches across a complex network of thinkers, and can be traced back far deeper into the past than the 20th-century. But I’ll focus on the four key figures who did most to shape the idea in its current form. They are the polymathic genius John von Neumann, British mathematician and computer scientist IJ Good, US computer scientist and science-fiction writer Vernor Vinge, and the popular futurist Ray Kurzweil.

Von Neumann was a mercurial titan of 20th-century mathematics and theoretical physics, best remembered for his work on the Manhattan project and game theory. And it’s Von Neumann who is believed to have first described a technologically induced ‘singularity’.

This comes to us not in Von Neumann’s own writings, but via a 1957 obituary by the mathematician Stanislaw Ulman. Recalling their regular talks, Ulman mentions:

‘One conversation centered on the ever accelerating progress of technology and changes in the mode of human life, which gives the appearance of approaching some essential singularity in the history of the race beyond which human affairs, as we know them, could not continue.’

It’s a brief but all-important first glimpse of the idea. Von Neumann’s leap to a ‘singularity in human affairs’ laid the foundation stone.

Remember, Von Neumann was a theoretical physicist. When he talked about a singularity, he did so with a precise understanding of the word.

In physics, a singularity is a theoretical entity found at the heart of a black hole. It’s a place where gravity becomes so intense that spacetime folds in on itself to create what is seemingly impossible: an object that has zero volume and infinite density. A point in spacetime, in other words, where the rules that govern physical reality simply break down.

And that’s what Von Neuman was talking about when he speculated on a technologically-induced ‘singularity in human affairs’. He meant a threshold that marked change so transformative that everything we know about human history — all the old models, rules, and norms that shape our collective and individual lives — no longer pertain. The Singularity, for Von Neumann, was a definitive break-point in the human story. Beyond it lay the unimaginable.

We don’t hear much about the Singularity again for a while. But in the meantime, the story was moved on in an indirect but consequential way by the British mathematician IJ Good.

A statistician of genius, Good worked with Alan Turing at Bletchley Park during WWII, and played a crucial role in breaking the German Enigma code. After that, he followed Turing into computer sciences. Here he is at the chessboard — he’s closest to the camera:

In 1966 Good published a now-iconic essay called Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine. It contained these lines:

‘Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an 'intelligence explosion', and the intelligence of man would be left far behind.’

Good had realised the insane recursive power of superintelligence to create even more powerful superintelligence, in an endless loop. His conception of the resulting ‘intelligence explosion’ — which would see intelligent machines render we humans as children in a world we could no longer understand — became deeply woven through conceptions of the Singularity.

That interweaving didn’t occur on its own. It happened over time, and most famously via the work of the maths professor and science-fiction writer Vernor Vinge.

In the January 1983 edition of the US science magazine Omni — it ceased publication in 1997 — Vinge wrote about the idea of a coming Singularity. And crucially, he linked it directly to the advent of superintelligence and the intelligence explosion that would result:

‘We will soon create intelligences greater than our own. When this happens, human history will have reached a kind of singularity, an intellectual transition as impenetrable as the knotted space-time at the center of a black hole, and the world will pass far beyond our understanding.’

This was a hugely significant step in the story. It was the first time anyone had linked Von Neumann’s conception of a ‘singularity in human affairs’ with IJ Good’s hypothetical intelligence explosion.

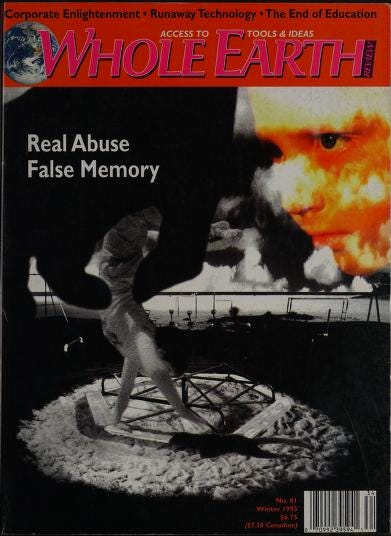

And in a 1993 essay in the Winter issue of the iconic Whole Earth Catalogue Vinge went further, arguing that it was the fusion of human intelligence with machine intelligence that must really define the Singularity.

‘From the human point of view this change [the fusion of human and machine] will be a throwing away of all the previous rules, perhaps in the blink of an eye, an exponential runaway beyond any hope of control… Von Neumann even uses the term singularity, though it appears he is still thinking of normal progress, not the creation of superhuman intellect. (For me, the superhumanity is the essence of the Singularity. Without that we would get a glut of technical riches, never properly absorbed.)’

A version of his essay eventually went viral on the early web, consolidating Vinge’s thinking as the mainline interpretation of the Singularity.

Vinge’s essay said the fusion of human and machine intelligence would lead to a ‘post-human’ era, and raised the possibility that this could be disastrous for we humans: ‘the physical extinction of the human race is one possibility’. In this way, the essay helped shape our current debate around AI doom, and is an ancestor to the post-human era speculations that Yuval Harari deploys in his smash hit Homo Deus.

Finally, in 2005 the futurist Ray Kurzweil published the book that pushed all these ideas into the tech-literate mainstream. The Singularity is Near endorsed Vinge’s conception of the Singularity as the coming fusion of human and machine intelligence. Never one to shy away from bold claims, Kurzweil declared that the Singularity would arrive in 2045. It’s a prediction he stands by today.

And so our contemporary conception of the Singularity was, at last, fully formed.

Kurzweil rounded out the idea as we know it today by gesturing, also, to its religious undertones. Under this view the fusion of human and machine intelligence is only the first step in a broader process that sees intelligent life travel to the stars, such that the entire universe eventually becomes a single, vast, and sentient superintelligence. These ideas drew on the mid 20th-century Catholic philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and his theory of the Omega Point: an ecstatic vision of final cosmic unification.

And with that our brief history of the Technological Singularity is complete.

But this history, as I made clear at the start, has been established for a reason. We’ve made a tour through some formidable thinkers here, and now I intend to tangle with them.

Because I believe that the conception of the Singularity we’ve ended up with via these thinkers — the conception that reigns supreme in 2024 — is far from ideal. It’s not the most coherent, or useful, version of the idea possible. So I’m going to suggest a new one.

Sure, it’s a bold move. But what’s the New Year for here at the Exponentialist if not for sharing our boldest thinking?

Aiagenteconomy.substack.com